I have to confess it was only twenty years ago, after

completing a book on the Mississippi Delta, that I began to understand the true

importance of such noteworthy sociocultural enclaves to a fuller, more textured

appreciation of the South as first, a place of many parts, and second, a place

all the more remarkable for it. For some time now, we have had the benefit of

some excellent writing about the Low Country South, the Appalachian South, the

Cajun South, etc. Now comes a new and most worthy addition to the bibliography

of special southern places that focuses on a narrow strip of sand, scrub, and

asphalt stretching along the Gulf Coast from roughly Gulf Shores, Alabama, to

Panama City, Florida, and known more with affection than condescension as "The

Redneck Riviera."

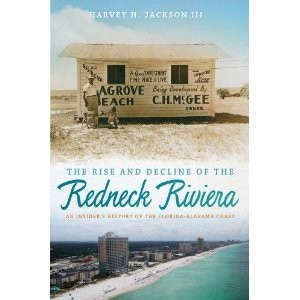

If ever a book found its ideal author, "The

Rise and Decline of the Redneck Riviera"surely did in the

person of my old friend Harvey H. "Hardy" Jackson. Hardy's attachment to the RR

goes all the way back to the mid-1950s when his Grandma Minnie bought herself a

lot and built a little cement-block cottage in Seagrove Beach, Florida, about

halfway between Destin and Panama City. Hardy has provided me with most of my

education about this alternately boisterous and idyllic little kingdom, and

I've got the scars on head, limbs, and liver to prove it. However, anyone who

might think that I am saying nice things about him or his book just because we

are friends or I owe him money (Best I can recall, more'n likely, it's the

other way around) can go here

or here

or here

to see that I am not exactly riding solo on this bandwagon.

Besides,

Hardy was nowhere around when I got my real introduction to this little sliver

of the world. That would've been along about 1988, when the fun family Cobbs

decided to vacation themselves at Gulf Shores. Leaving our teenager and a

couple of his pals to their own devices and God knows what else, Mom and Dad

opted for an adults-only excursion to a legendary watering hole squatting darn

near right on the Alabama-Florida line and thus known officially as "The

Flora-Bama Lounge, Package, and Oyster Bar," although so far as I know, no one with any real acquaintance

with the place has ever bothered with anything beyond "The Flora-Bama." The

F-B's reputation for the wild and woolly definitely preceded it, and sure

enough, the ambience was decidedly white-working-class-after-a-twelve-pack up

to and including all of the bras dangling from the ceiling, each suggesting an

evening when somebody, perhaps everybody, had gone home with a story to tell.

However, the real persona of the place didn't really come through until,

standing on the back deck, we observed what looked to be two thirty-something

females doff their bikinis and make a rather elaborate production of rinsing

them out in the same churning sand and surf from which they had just emerged,

before donning equally skimpy shorts and tops and heading straight for the back

door of the Flora Bama. Upon entry, they proceeded directly and

un-self-consciously across a densely populated room to the bar, as layer after

layer of Bubbas played Red Sea to their Charlton Heston. Not surprisingly,

however, they were speedily re-enveloped by a swarm of these eager

hyper-hormonal young swains who simultaneously tossed pickup lines at them and

elbows at each other as they bid to escort these fair damsels into a promised

land flowing full and free with the best that Anheuser-Busch and Miller Brewing

had to offer. After experiencing considerably greater difficulty in making my

way across the room for a refill, I asked the barkeep if he had ever seen

anything like what had just happened, and his barely discernible shrug

suggesting "not since last night" told me that I might as well have

"candy-assed professor" stamped on my forehead.

I'd

like to think I maintained my cover a little better a few years later when

Hardy took a bunch of us to hear "The Trashy White Band" perform in Destin at a

dive called The Green Knight, where entering and departing patrons were saluted

by a larger than life statue of same. As for the Trashy White Band, much of

their repertoire isn't printable here or anywhere else where even the faintest

whiff of decency survives, although many's the time in a heated faculty

meeting, I've wanted to launch into their most requested number, "I'll Be Glad

when You're Dead, You Son of a Bitch, You!" The Green Knight went nite-nite

about twenty years back, but, the Flora-Bama, its fame enhanced by the now legendary

annual interstate Mullet Toss, still stands as a resolute citadel of what

historian Pete Daniel calls the "low-down" dimension of southern culture, and

by golly, I'm looking forward to a return visit this fall when the Southern

Historical Association meets in Mobile. [The Missus says I'm not going to the

Flora Bama without her. I say there is strength in numbers, although I'm not

really sure that this actually applies when the rest of the contingent are also

representatives of the candy-assed professoriate.]

One

reviewer of Jackson's book suggests that the Flora Bama symbolizes "the

resilience" of the Redneck Riviera. Burned down by a competitor in the 1960s

and "gutted" by Ivan in 2004, today it remains a "socially egalitarian

demilitarized zone." That metaphor is apt in many respects, but the rowdy,

raunchy aspects of the area's social scene hardly do justice to the realities

of a place where the newest additions to the Lower South's emerging post-World

War II white middle class established their family vacation traditions in

largely unadorned cottages in little communities like Seagrove, where trailers

and outhouses were verboten but hanging swimsuits and towels on the front porch

to dry was just fine. The kids could chase each other and scream to their

hearts' content under communal adult supervision, and the smattering of local

eateries could satiate your hunger for any kind of seafood, so long as it be

fried.

Alas, the same economic progress that had made a vacation or vacation cottage in the area a possibility for so many Deep South families would soon be threatening its unpretentious, laid back ambience. Jackson lays some of the blame for this on the 1960 film "Where the Boys Are," starring Connie Francis and ol' Mr. Tan Man himself, George Hamilton, for a massive outbreak of spring-break fever, which suddenly made it "cool" for southern collegians to undertake annual pilgrimages to beaches theretofore thought to be a mite frigid for serious partying in March. Although local merchants and innkeepers indulged in all manner of obligatory tut-tutting about all the drinking and "casual sex," behind closed doors, they were salivating to beat the band as the cash rolled in. In short order, Jackson writes, "What started as a rite of spring" would "become an event popularized and promoted to make a lot of people a lot of money." The area had never been without its profiteers and schemers, of course, but the mammonism had really kicked in by the end of the 1960s, and the places where relative peace and quiet could still be had became progressively more difficult to find.<br />

Sorely

distressed by this trend, some locals actually saw a brief glimmer of hope that

it might at least be slowed if not completely reversed at the beginning of the

1980s when developer Robert Davis announced plans for "Seaside," a planned

development of shops, restaurants, and homes that he promised would mark "a

return to the traditional seashore cottage design of yesteryear." The idea of

narrow streets and small lots was meant to encourage, or simply coerce, human

interaction within the new community which, Davis insisted, was to be a "real

town" where folks young and old might still get "in touch with the real

pleasures in life." Unfortunately, a venture that smacked of a sort of upscale

version of what the good folks in Seagrove and other less pretentious

communities had been enjoying for more than a generation wound up as what

strikes me as a smug yuppie enclave whose residents and regular tourist

visitors turned every visit to the beach or the market into a Ralph

Lauren/Lilly Pulitzer fashion statement. Soon the Seasiders were putting up

signs and hiring security personnel in order to ensure that their relatively

downscale Seagrove neighbors, with their Wal-mart flip-flops and cut-offs

stayed among their own kind. As for friendly front-porch chitchat within the

confines of Seaside itself, the deafening roar of the air conditioners would

have drowned it out had anyone been fool enough to sit outside under a tin roof

that was itself struggling not to melt away under the unforgiving gaze of a

broiling summer sun. Ironically, what was purported at the outset to be a place

that harkened back to the era of greater human interaction and community had

quickly begun to give off what one travel writer felt was a decidedly

"plastic/Stepford Wives" vibe.

There

would be other, bigger additions to this genre, including Watercolor, a much

larger and more richly amenitized development bankrolled by the St. Joseph

Paper Company. While promoters for ventures like Watercolor (whose designers

had helped to lay out a Disney development near Orlando) and Seaside fell over

themselves in emphasizing their not-always self-evident "traditional" aspects,

as Jackson notes, "the tradition they followed was that of the status-defining

enclaves on the north side of Atlanta and the south side of Birmingham, which

were home to Dixie's new elites." The Redneck Riviera has quite a track record

of bouncing back from the cyclonic assaults of Mother Nature including Eloise,

who de-roofed Grandma Minnie's cottage in 1975, and Ivan, which leveled the

Flora Bama in 2004. Happily both have been restored, and in fact, as Jackson

deftly shows, the necessity of rebuilding after these natural disasters has in

fact spurred the process of growth and economic modernization on several

occasions.

There is always the chance of ol' Ma Nature showing the

locals that they really haven't seen anything yet, but as Jackson manages to

reveal without being especially preachy about it, the major menace to the

special qualities of the Redneck Riviera has for some time been the humans who

wish to popularize, exploit, or stake exclusive claims on its natural riches

and appeal. This reality became indisputably apparent in April, 2010. As no

less an entity than the Supreme Court itself mulled over claims of some Destin

beachfront homeowners that their property lines extended all the way to the

water line and thus they were entitled to opt out of public projects aimed at

restoring the area's seriously eroded beaches, an explosion at a British

Petroleum drilling site off the coast of Louisiana quickly raised the threat

that all parties to this dispute might soon find their beloved beaches soaked

with oil. The ominous approach of a gigantic, environmentally poisonous mass of

oil provided both backdrop and storyline for the last chapter of Jackson's

book, wherein he captures masterfully all the anxieties, both economic and

purely emotional, that enveloped the area while he was wrapping up his

manuscript. The feelings that surfaced as the slick drew nigh underscored the

abiding affection of old-timers like Jackson himself for this place, which had

survived so many outrages, natural and human, and now seemed to be facing the

kind of devastation from which there might be no bouncing back.

When,

(wouldn't you know it?) the area had managed to escape or beat back the worst

of the threatened despoliation, local promoters were all for a blowout Jimmy

Buffett concert at Gulf Shores, aimed at showing that the Redneck Riviera was

once again open for business. Steeped in the area's history, Jackson does not

miss the irony in an image-conscious local writer's complaint that a subsequent

appearance of blue-collar fave Lynyrd Skynyrd would simply attract "every

toothless redneck from a hundred miles," each one packing his own eats and a cooler full of "Busch and Natty Light,"

meaning that the only real hope of making a buck off the event might be to

"open a cheap cigarette and Confederate bandanna shop."

Despite such snarkiness in some quarters and a little rain besides, the concert ultimately "went off without a hitch," Jackson reports. Clearly pleased to find a reason to believe that some of the old spirit and persona of a place he has loved so long and well might yet survive, he concludes with the observation that the audience for Lynyrd Skynyrd actually "looked a lot like the one that had gathered to hear Jimmy Buffett. . . . and not unlike the people who had always slipped down to the Redneck Riviera. They were the children, and in some cases the grandchildren, of beachgoers who over the years came to the coast to swim, fish, ride rides at the amusement parks, dance at the Hangouts, listen to the Trashy White Band at the Green Knight, and throw a mullet at the Flora-Bama."