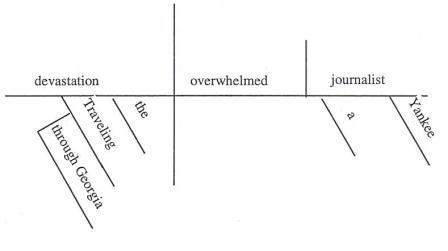

"Traveling through Georgia, the devastation overwhelmed a

Yankee journalist."

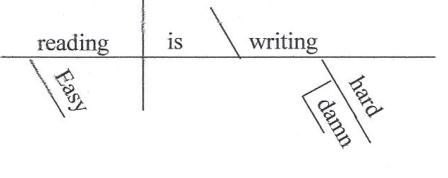

Every time the ol' Bloviator encounters a sentence such as the above, be it in a student paper or (gasp!) the New York Times, he realizes that historians of American education will one day mark the widespread abandonment of the practice of diagramming sentences as a major milestone along its path to decline. Even a hurried, rudimentary attempt to decline the sentence above would have demonstrated that, as written, it had devastation rather than the journalist doing the traveling.

In other words, as the saltier grammarians might put it, the writer had let his participle dangle where it didn't belong and in doing so had mangled the meaning of the sentence into absurdity.

To

offer but one additional example, courtesy of

Slate, of the

potential benefits of sentence diagramming, had there been some coercive

measure sufficiently horrible and threatening to force her to diagram one of

her sentences, Sarah Palin might have actually seen what a god-awful mess they

were. For instance,

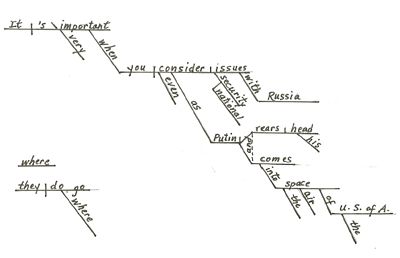

It's

very important when you consider even national security issues with Russia as

Putin rears his head and comes into the air space of the United States of

America, where--where do they go?

would look like this: :

On a broader scale, the practice of breaking sentences down into an organizational schematic--think about dissecting a frog absent the upchuck factor--was a vital step in the process of teaching students not just how the parts of speech function within the sentence but how sentences were to be constructed so that the writer or speaker's meaning was clearly and correctly conveyed. Admittedly, it was a tedious, time-consuming task for students to perform and for teachers to grade, and it also required not just an understanding of the parts of speech themselves but a disciplined faith in the importance of using them properly. Hence, as we moved into the post-structural age, in which all forms of communication were valued equally and self-serving clichés such as "thinking outside the box" conveniently devalued many of the traditionally most challenging aspects of the teaching and learning process, critics of diagramming began to ask "Why do we place such a great emphasis on diagramming? I remember it being a great source of frustration for me in school. And I don't want to pass that on to my children."

God forbid that we subject our little darlings to anything that might prove challenging, and therefore frustrating, to them--and, ultimately, us. Besides, reasoned another skeptic, "If the goal is communication, why does the student have to know that what he is saying is a noun or verb, etc. . . . If a student can properly write a sentence, why does he have to know all of the parts of that sentence? I just don't get it."

That this argument actually came from "an engineer and a teacher" renders it all the more distressing. Based on this logic, why worry about how a cantilevered bridge actually works so long as you know what one looks like? Why dissect a frog so long as the student can tell live ones from dead ones and understands that their legs taste damn good fried? For that matter, why should a pilot have to understand the intricate mechanics of his plane so long as he knows which levers to pull and buttons to push?

It was clearly easier on all concerned to jettison the old-fashioned and cumbersome process of breaking sentences down into visual models and proceed with vigor to the more subjective, loosey-goosey exercise of reading Tom Sawyer or David Copperfield. The justification here was that someone (no one seems to know exactly who) once declared that "the great writers of this world do not become great writers by diagramming sentences, but rather by reading good books, using their writing tools and practicing their writing."

It is true enough that some largely self-taught writers of the current generation say that they honed their skills by reading tons of great literature and trying to emulate it in their own writing until they found their own "voice." This might be true, but who is to say that their appreciation of the literary giants might not have been considerably richer and ultimately more instructive had they come to their task with a fuller understanding of the mechanics by which it was produced. Moreover, I'm not buying into the notion that most of the great writers we're talking about here were bereft of any experience in sentence diagramming. Take for example, Gertrude Stein, who once insisted, "I really do not know that anything has ever been more exciting than diagramming sentences." I really don't know if I'd go quite that far, Gertie, but I do know that a lot of writers in the late nineteenth and even early twentieth centuries had experiences with diagramming sentences, not just in English but in Latin, German, and other languages as well.

For that matter, one need only examine the literary precision in the writing of many everyday folk in that bygone era to see evidence of some hard-core training in word usage and sentence structure. From that perspective, letters to the editor from that era are frequently far more grammatically felicitous than anything written by most professional journalists or editors today. Take, for example, this February 14, 1896, missive to the Marion County [Ga.] Patriot from Ms. OB's rather modestly educated great-grandfather, Rev. Thomas R. McMichael:

Mr. Editor, These are perilous times. . . . It seems that our country is becoming the boasted asylum of the oppressed of all lands. Our doors have been thrown open and men of every clime have been invited to come and partake of our bounty and share in our glory and they have not been slow to accept the invitation. Thousands are flocking to our shores, bringing with them every type and phase of character, and every conceivable habit of life and shade of political and religious opinion. . . . Thus we have a similarly heterogeneous population of very nearly every nationality and tongue, of every color, from lily white to ebony--of every degree and form of vicious ignorance, of every type and grade of English, French and German infidelity, intermixed and overlapped with the exuberant vices of our fast American life.

Once you get over being shaken by the decidedly contemporary ring of the sentiments expressed, ask yourself if you typically find such views expressed with nearly such organizational care and grammatical precision today. The good Rev. may have been a nativist, but as his numerous published sermons also attest, at least he was a literate one, and I'm guessing that he would be more than a little pleased to learn what a first-rate editor his great-granddaughter turned out to be. Though he would seem to have little in common with the superbly educated Bowdoin College Phi Beta Kappa Nathaniel Hawthorne, Rev. Tom would surely have seconded Hawthorne's observation that