Well, I always heard, I ain't too

sure

That a man's best friend is a mangy cur,

I kinda favor the hog myself,

How 'bout a hand for the hog?

Roger Miller, "How 'Bout a Hand for the Hog?"

In what has already become a classic, if not a damn near iconic piece of writing that at once makes me both envious and proud, my friend and former PhD student Jonathan Bass seized on the title and refrain of the little Roger Miller ditty excerpted above as the inspiration for a lively and insightful examination of "the enduring nature of the swine as a cultural symbol in the South." (Bass's essay appeared way back in 1995, by the way, in Southern Cultures, a wonderful journal that anyone from pointy-head to pipefitter who happens to be interested in the South will find extremely readable and engaging.) I thought immediately of Jonathan's piece a couple of weeks ago when my wonderful wife fulfilled a longstanding wish of mine by presenting me with (see above) a truly striking piece of sculpture, the likes of which I had gazed longingly upon for years as we roared up and down the highways passing up many a golden opportunity to stop and peruse the pigs, chickens, dogs, and various other forms of wildlife and livestock made available to discerning purchasers by the high-minded purveyors of concrete yard art.

Aside from what it says about the recipient's personal tastes, owning this little fella is clearly in keeping with a thirty-six year career devoted to talking and writing about all things southern. Whatever else our giftee may have learned over that span, he knows absolutely that there are few things even arguably as southern as a hog. As far back as the 18th century the condescending Virginian William Byrd aspersed his Tar Heel neighbors to the south by noting that they "live so much upon swine's flesh that it don't only incline them to the yaws, and consequently to the . . . [loss] of their noses, but makes them likewise extremely hoggish in their temper, and many of them seem to grunt rather than speak in their ordinary conversation." Allowing for Byrd's hyperbole and Old Dominion hauteur, it's still fair to say that the hog's relationship with the South and its people has not always been healthy for either. In fact, it was entirely fitting that my newly acquired representational porker, which weighs in at 104 pounds, damn near put hernias on me and my neighbor Joe as we tried to wrestle it out of the back of my little Volkswagen Beetle.

Although one of the great unspoken tenets of southern history and culture might well be that the hog giveth and the hog taketh away, these critters were not indigenous to our neck of the woods at all, but first came in the company of De Soto and other Spanish explorers for whom they became mobile meals-on-hooves. Those who strayed or were abandoned by the Spaniards proved to be some of the multiplying-est beasts on the planet. Reverting quickly to a feral state and finding the lush mast of the virgin southern forest greatly to their liking, they were soon a prime target for Native American hunters, although these piggies on the prowl could also become eco-competitors, playing hell with the Indians' dependence on acorns and other nuts during times when meat was scarce.

When the second - and, for the Indians, far more deadly and destructive - European influx came, the business of conquering and rolling back the frontier entailed not only hunting the wild hogs along with other wild game, but, as time passed, claiming and managing them as livestock. There were limits to the degree of domestication required at this point because throughout the antebellum South it was a matter of both law and custom that livestock were allowed to roam free across any fields and woodlands not protected by fences, which were then the responsibility of the property owner to erect and maintain. For small landowners this meant raising hogs for food without having to allocate precious acreage or a portion of the crops grown on that acreage to their upkeep. For the pigs, of course, it meant, as the old southern equivalency of " You're on your own," put it, "Root hog or die."

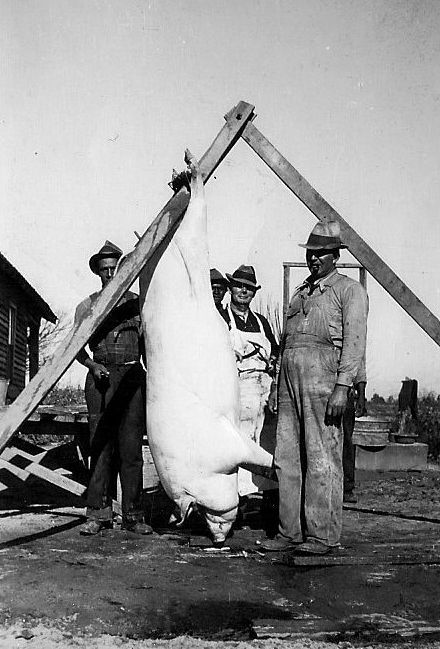

This the hogs did until they were rounded up in late fall or early winter in anticipation of the first cold snap that promised to hang on long enough to get the meat "worked up" before it spoiled. (It sobers me [almost] to think that mine is the last generation of southerners to have any idea what climatic conditions are denoted by "hog killin' weather.") Save for the advent of refrigeration, the fundamentals of hog killing on the farm remained relatively unchanged over the better part of two centuries. (The photo below dates to the 1940s and shows my Daddy on the right with what, with his remarkable gift for understatement, he might well have termed "a right good-sized hog.")

As I recall it from the 1950s, the ritual still affirmed above all else that, ugly and nasty as an ol' hog might be, it is one more thoroughly edible creature. From its feet to its brains, the slain animal contributed practically every external protuberance, internal organ, and even its intestines to somebody's table. Although "fatback," the subcutaneous fat running along the hog's back was considered the poor man's bacon, those who laid claim to the leaner shoulder, loin and other succulent cuts that generally came from the upper two-thirds of the body were said to be eating "high on the hog," (a phrase originating in England that naturally found widespread usage in the South). Farther down, the jowls, belly, and feet were generally considered more humble fare, even though they also graced many a fine table themselves. Meanwhile, the soft "belly fat" supplied the lard which was used for cooking grease and cared little whether it was clogging the arteries of a yeoman or a squire. It also came in handy for greasing a wagon wheel or soothing a burn. Nothing gave better evidence of southerners' absolute determination to extract every last calorie from the unfortunate hog than the insistence consuming the small intestines, or "chitlin's"--that's "chitterlings" for you Yankees. This process was every bit as filthy and stinky in 1950 as it had been in 1850, and anyone who has ever encountered the pungent and pervasive fragrances emanating from a kitchen where chitlin's were boiling may well have witnessed the exceedingly rare spectacle of flies actually trying to get out of the house.

As someone whose adolescent duties included "slopping" several of them every morning, I am well aware of the hog's severe deficiencies in manners and personal hygiene, but when it came to caloric return on investment, a big ol' porker was mighty hard to beat. Scientists have supposedly calculated that anyone who is eating pork is getting roughly 24 percent of the energy equivalent that the hog derives from a grain diet as compared to only 3.5 percent from a cow on the same diet. It was small wonder then that for every pound of beef, antebellum Southerners consumed five pounds of pork. All of this points to one of the less obvious ways in which the Civil War changed the South. In addition to destroying slavery, which was by far the single greatest source of wealth in the region, it also decimated the hog population, which fell prey both to invading Yankees, who were far less likely to leave with the family silver under one arm than a nice fat pig, and to the desperately hungry Confederates reduced to hog-rustling in their own land.

It would be misleading to say that it took many years for the porcine component of the region's diet to recover, for in fact it never did, at least not in terms of the general availability of pork on southern tables. For example, the war cut the hog population of Georgia from just over 2 million down to just over 1 million. This figure would rise slightly over the next two decades, but unfortunately the human population was growing much faster so that while there were roughly 2 hogs for every Georgian in 1860 there was only one by 1880.

This greatly diminished hog-to-human ratio was not simply a reflection of the lingering effects of losing roughly a million of the critters during the conflict itself, but of the long-term effects of the economic changes wrought by the war. With slavery gone, land value was now much more critical to wealth in the South, and hence there came a sharp reversal of the old pre-war practice of allowing grazing livestock to roam free across property lines. New "fence laws" now put the burden of keeping animals off the property of others on the owner of the animal rather than the owner of the property. Keeping livestock thus became infinitely more difficult for the small landowner who simply had no acreage to spare for grazing or foraging and no grain to spare for feeding the animals otherwise. Deprived of their hogs, small farmers could no longer practice what has been called "safety-first" agriculture by concentrating primarily on producing enough food to sustain the family before venturing into growing cotton for cash. Indeed, agreeing to grow cotton was the only hope of securing the credit that was now necessary to keep food on the table throughout the year. Because cotton prices were in general decline, the inability to repay their notes soon drew these small landowners into a downward spiral of dependency and debt, all too frequently leaving them to work as sharecroppers on someone else's land and pay often prohibitively high "credit prices "on fatback, lard, and other hog-derived foodstuffs that they or their ancestors had once produced for themselves at virtually no cost.

As hogs grew harder to come by, the "barbecue" became even more of a rich man's affair--or at least a more emphatic demonstration of his affluence to his lesser neighbors--than it had been in the antebellum era. Because barbecues were typically staged in warm weather, there was little chance of preserving any part of any hog not consumed on the spot. Barbecues became an election year staple, and the less well-to-do white folks who had not tasted lean pork since the last campaign could be counted on to turn out in force to swat the green flies off their 'cue and nod approvingly as the likes of Georgia's Gene Talmadge gave blacks, not to mention Atlantans and other city slickers "down the country." In fact, ol' Gene's pure political genius never shone more brightly than when he turned what was an act of pure recklessness, involving hogs no less, into a prime example of why he should be regarded as "the little man's best friend." Vowing to raise hog prices while serving as Georgia's Commissioner of the Agriculture in 1930, Talmadge had secured no official authorization from the higher-ups before spending some $14,000 in state funds to buy 82 carloads of hogs in Georgia at higher than the local market value and then ship them to Chicago where prices were notably better and thus, presumably, the expenditure would be recouped while Georgia hog prices had been boosted. As it turned out, however, Talmadge had not exactly factored in the uneven and inferior diet of the Georgia porkers in comparison to the plump corn-fed beauties fresh off Midwestern lots, and the Georgia hogs' severe weight loss during transit wound up leaving the state down at least $10,000 on Gene's unapproved investment. As he went on to win the governor's office four times, his clueless opponents persisted in charging Talmadge had "stolen" from the state in this incident, only to have him repeatedly delight thousands upon thousands of eager-to-believe rural Georgians by declaring unapologetically, "Shore I stole. . . . but I stole for you! You men in overalls. You dirt farmers!"

Although he knew a little bit about stealing himself, the genial, folksy Marvin Griffin, who had won the Georgia governorship with Talmadge machine support in 1954, failed in his bid to come back for a second round of merry malfeasance in 1962. Griffin put the punditry's complex analysis of his defeat to shame when he simply explained in terms every southerner could understand that "some of the people who ate my barbecue didn't vote for me."

An affinity for pork once seemed so synonymous with southern life as to become a definitive regional character trait and a colorblind one at that. When the young black protagonist of Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man arrives "up North" he immediately encounters a lunch-counter server who sizes him up as a freshly arrived southerner and pushes him to order "the special," consisting of "pork chops, grits, one egg, hot biscuits and coffee." The young man recoils from this obvious regional stereotype, defiantly ordering toast and orange juice instead, but wondering to himself "could everyone see that I was southern?"

Southerners also embraced porcine symbolism to set themselves apart from their northern brethren, as in the ageless tale of the know-it-all Yankee who observed a farmer patiently holding a young hog up to an apple tree while it munched in rather leisurely fashion on the hanging fruit. "Excuse me, fella'," sez the Yankee, "wouldn't it save time if you just picked those apples yourself and tossed a bunch of them into his pen?" "Maybe so," deadpans the farmer, "but what's time to a hog?" At its very simplest, this story shows a supposedly backward southerner getting the best of a Yankee by simply playing to "type," but at its most profound, it suggests dramatically different approaches to life, particularly attitudes about the relative importance of means and ends and, of course, the true meaning and value of time itself. (By the way, in case you question the regional spin here because this story makes you think of the old Playboy cartoon in which one partially submerged hippo admits to another, "I just can't get it through my head today's Tuesday," I need only point out that the common hippo population is heavily concentrated in southern Africa, after all.)

Suffice it to say that although I'm not sure how the neighbors feel about my new piece of statuary, I plan no apologies in any event. Au contraire, as we like to say up in Hart County, I might just mount a campaign to have the hog declared the official symbol of the South. Look at it this way, it's a lot less controversial than the Confederate flag, a lot more representative than a bimbo in a hoop skirt, and the likelihood that someone will try to take it away from us is, at best, fairly minute.