In

conjunction with the sesquicentennial of the recent unpleasantness which is now

upon us, the New York Times has set up a special series on the web following

the course of events as they unfolded in late 1860 and flowed across the next

four and half years. The ol' Bloviator sent them the following

little piece, pointing out that the secession crisis facing the nation at the

end of 1860 had been building for quite a while and that it was actually

northerners who had first begun to practice the politics of sectionalism,

albeit under the guise of a nationalist agenda.

You can read the posted version here or slog through the O.B's virginal prose below:

Historians

once routinely blamed southerners for introducing the virus of sectionalism

into the American body politic while praising their northern adversaries for

their selfless devotion to the Union. More recently, however, Peter Onuf and

others have argued that New Englanders were actually the nation's most

"precocious sectionalists," even though their sectionalism was often cloaked in

the soaring rhetoric of early American

nationalism. writers like geographer Jedediah Morse shamelessly touted their native New England

as the quintessential model for American national identity and character,

pointedly contrasting its Yankee "industry . . . frugality .[and] piety" with

the slothful, irreligious southern slaveholding culture of "luxury, dissipation

and extravagance." "O, New England!" How

superior are thy inhabitants in morals, literature, civility and industry."

Employing similar juxtapositions of New England virtues and southern vices,

later writers, including Harriet Beecher Stowe, helped to inspire and nurture

what would eventually become a broader "northern" vision in which the northern

states became synonymous with America while the southern ones stood as its

complete antithesis.

By 1823 New Yorker Gerrit Smith could already remark on the

almost "national difference of character between the people of the Northern and

the people of the Southern states." Lost in translation here, as historian

Joyce Appleby noted, was the sense that by that point "Northerners

imaginatively thought of their 'nation' as the United States, leaving the South

with its peculiar institution and a particular regional culture."

Before the talk of secession at the Hartford Convention of

1814 blew their cover, New England Federalists had succeeded in using a nationalistic façade to conceal a sectional

political agenda that could best be served by a central government powerful

enough to protect and advance their trade and shipping interests at home and

abroad. In the years to follow, New England's eloquent champion, Daniel

Webster, consistently cloaked his support for sectional policies such as

protective tariffs and internal improvements in the language of national

interest. By the middle of the nineteenth century though, Webster made no

secret of his hope for a politically cohesive "North" rooted in a coalition of

northeastern and western free states (settled in part by New England émigrés)

intent on protecting the interests of free labor and halting the spread of

slavery. Webster's wishes were realized in the meteoric ascent of the

Republican Party whose strikingly concentrated northern support base made it,

as historian David Potter observed, "totally sectional in its constituency."

Yet with their party's strength centered

in some of the nation's fastest growing states, Republican leaders

realized that northern interests might soon be calling the shots in national

politics. Thus, as Potter noted, they could "support the Union for sectional

reasons," while southerners clearly could not.

Although they were relative Johnny-Rebs-come-lately to the

business of what might today be called regional "branding," as they scrambled

to find a legitimate, unifying antecedent and symbol for their increasingly

particularized and embattled region, southern writers and orators threw

themselves into the politics of sectional identity with determination and

verve. Some, like George Fitzhugh and Thomas R. Dew, invoked the slave society

of ancient Greece as a laudable analog, but, as cultural icons go, an Athenian

in toga and sandals is no match for a dashing English Cavalier.

Gaining

currency amid mounting criticism of the South in the 1830s, the Cavalier legend held that white

southerners were actually far superior in breeding to their northern

detractors. After all, southerners could trace their bloodlines back to

the old Norman barons through the Cavalier-aristocrats who had emigrated to the

southern colonies after losing out in the English Civil War to the middle-class

Puritan "Roundheads" or "Saxons" whose kinsmen had ultimately settled the North.

Although outside Virginia few southerners could show evidence of Cavalier ties

and even fewer Cavaliers likely had Norman ties, as early as 1835 Louis

Phillipe was warning that the Puritan North-Cavalier South cultural divide

meant that Americans, "as a people, have conflicting interests and ambitions

and unappeasable jealousies." His words seemed prophetic indeed in light of a

Virginian's assertion in 1863 that "the Saxonized maw-worms creeping from the

Mayflower" could claim no "kinship" whatsoever with "the whole-souled Norman

British planters of a gallant race." Zeal for the Cavalier legend had also been

stoked by the enormously popular writings of Sir Walter Scott, whose tales of

Scotland's struggles against English oppression seemed to evoke the South's

struggles against the North so effectively that Mark Twain would later blame

the Civil War primarily on southerners' affliction with "the Sir Walter

disease."

If, however, the Cavalier legend had become what James

McPherson called "the central myth of Southern ethnic nationalism" among more

affluent or literate southerners by the 1850s, efforts to promulgate it more

widely ran afoul of such regional realities as a relatively small urban

population, a per capita circulation for newspapers and magazines that was less

than half the northern rate, and an illiteracy figure roughly three times the

northern average. Finally, there was also reason to doubt the resonance of the

Cavalier ideal among the white yeomanry which had grown politically restive

during the 1850s as soaring slave prices dashed their aspirations to climb into

the planter class. Indeed, a rather clueless proposal to feature the figure of

a "Cavalier" on the official seal of the Confederacy was ultimately derailed by

concerns that the slaveless two-thirds of the South's free population might be

less than enthusiastic about taking up the cause of an institution in which

they had no immediate stake if the symbol of said cause bluntly reminded them

of precisely that fact.

Ironically

enough, the common feelings of affinity

and obligation to the Union consistently expressed by northern troops during

the Civil War may have represented a fulfillment of the adroitly concealed

sectional ambitions of their forbearers. Among the Confederates, meanwhile, the

frequently echoed sentiments of the Georgia private who declared "if I can't

fight in the name of my own state, then I don't want to fight at all" testified

to the difficulty of creating what Alabama fire-eater William Lowndes Yancey

described as a shared "southern heart." It would take a fierce

four-year conflict ending in a bitter and ignominious defeat to forge anything

approaching the sense of kinship and common cause that the white South's

leaders had tried to instill before its ill-fated struggle for independence

began.

As it turns out, the

real story here is not that a guy who reads the Dawgvent religiously and has "Waltz across Texas" for his

ringtone, actually wrote something that appeared under the New York Times

masthead. That's actually happened

before, believe it or not. For me the most striking aspect of the whole

affair was the reaction to the OB's humble little offering. This reaction, by the way, sprawls over six

pages and reflects the views of no fewer than 139 commentators. These responses go well beyond straightforward stuff like "Put a sock

in it, Redneck!" Most are in fact quite lengthy-- some are damn near

encyclopedic-- and reasonably eloquent.

What jumps out at me is the fact that now it seems it's not just

southerners who want to keep fighting the Civil War. There's also a good number of Yankees just

itching to mix it up a little more as well. At first blush, this may seem a bit

strange in that the victors are supposed to content themselves with

self-satisfied gloating while the losers whine, alibi, and demand a rematch

they really don't want. (Contrary to popular wisdom, southerners have hardly

been unique in upholding their end of this bargain. Check out the Irish and the Scots, for

example). This emergent--and, I'd say

growing--chip on northern shoulders may actually reflect a sense that whatever

their ancestors may have thought they accomplished militarily in 1865, has, a

century and a half thence, largely been neutralized by a southern cultural and

political counterattack. One of the commenters

on my piece captured this frustration quite well:

No

question that the culture of the North, based on doing your own work, was

morally and culturally superior to that of the South, based on enslaving others

and making them do your work for you. It's not as though one side wasn't in the

right, and the other wrong. Sadly, the South won the cultural "war"

in the 150 years following. Now NASCAR, religious fundamentalism,

anti-intellectualism and redneckism have infected the entire nation. Perhaps it

would have been better to just let the less-civilized South go.

In short, the spoils of war have been spirited

away. Jeb Stuart is back and raiding the Yankees' corn cribs and smoke houses

with absolute impunity. About the only

difference this time around, it seems, is that the big tussle , otherwise known

as the "irreconcilable conflict," ain't between the Blue and the Gray, but the

Blue and the Red. Consider Gerrit Smith's

1823 observation above about the "almost national

difference of character" between the northern and southern people. Then, reel forward 187 years and note the

very first observation on my disquisition, which came from a guy in St. Paul:

The North and

the South are as culturally apart as any two nations. We have little in common,

as far as I'm concerned, except our contempt for each other. One look at the

consistent Blue State / Red State map makes it very clear: we don't belong

together. That sounds radical today, but I think 150 years from now our

descendants will wonder why it wasn't obvious to us. The North was right to

emancipate human beings held as slaves; having done it, we should have not only

allowed the South to secede, but demanded it.

Lest you think this

dude represents some-ultra-pissed off Yankee lunatic fringe, note the

observations the senior

editor of Foreign Affairs Mark Strauss, who noted in 2000

that while "W" had lost the

popular vote nationally by 500,000 votes while winning in the old Confederacy

by 3.1 million votes. It was obvious, therefore, that "the North and South can

no longer claim to be one nation." Rather, they "should simply follow the

example of the Czech Republic and Slovakia: Shake hands, say it's been real and

go their separate ways." If this meant that the North wound up seceding this

time around, then so be it. Likening the South to "a gangrenous limb that

should have been lopped off decades ago," Strauss supported his indictment with a lengthy list

of particulars, including, "The flow of guns into America's Northern cities

stems largely from Southern states" and "the tobacco grown by ol' Dixie kills

nearly a half-million Americans each year."

Surely there is reason

to suppose or at least hope that Strauss was operating with tongue partially in

cheek. Not so, I think with the sociologist

who described Sarah Palin in 2008 as culturally at least, 'a snowbound

southerner" or with this commenter, reacting

not so much to my piece but to other comments on it, who served up a classic

example of liberals' to "southernize"

everything they don't like about contemporary America. Note the following and

the rejoinders it attracted:

But

how does one account for the ignorance of the South coming from the mouth of

Sarah Palin?

Ditto. And how

does one account for the ignorance of the South (hate-speech, racism, religious

intolerance) coming from the mouths of all of my Italian-American relatives and

their friends in New York? The first time I ever heard the "n-word"

as a child was in New York. What do you have to say about the urban race-riots

and hate crimes in the North during the 60's, 70's, 80's and early 90's? The

twin diseases of hate and ignorance exist in every culture, every region and

every section of the United States....As for Southern succession(sic) solving the

problem of today's political polarization: the last time I checked, Michele

Bachman was from Minnesota.

The

points I was trying to make quickly fell by the wayside as the commenters went after

each other like Grant and Lee, but when anybody bothered to notice the piece

that actually ignited this conflagration, reactions to it were fairly equally

divided between accusing me of bashing the South and charging that I was a

southern apologist. Perhaps the

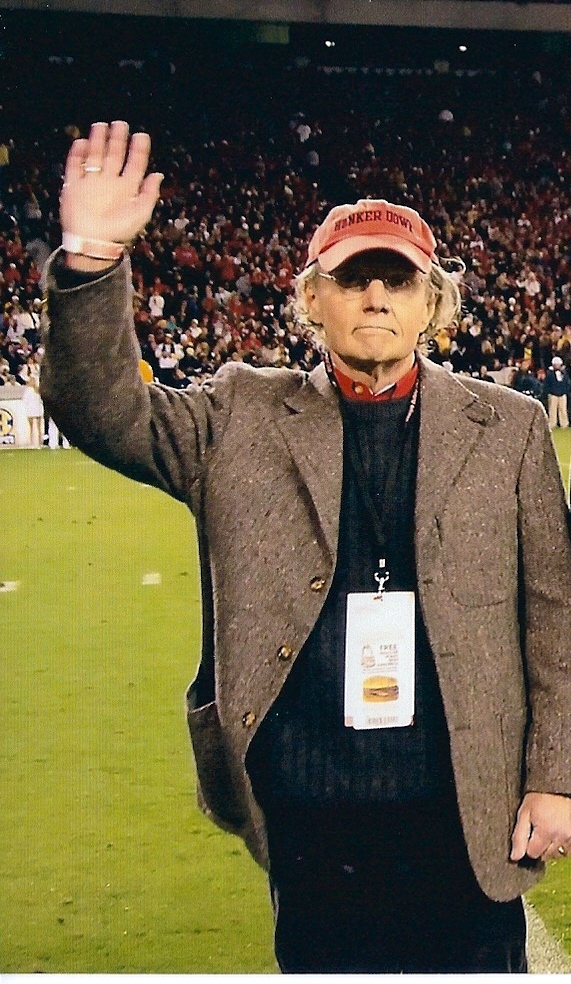

unkindest cut of all, however, came from the person who asked, " "Dr Cobb, would you consider changing your thumbnail photo?

Whenever I'm scrolling down the page, I always think it's Joe Lieberman."

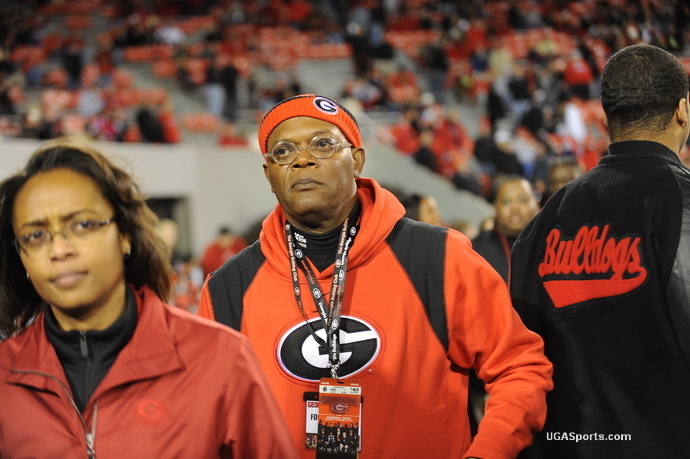

Regrettably, I was not the only celebrity in

attendance that evening, and I couldn't help but feel a little sorry for Samuel

L Jackson, in that my presence doubtless overshadowed his to a great extent.

Regrettably, I was not the only celebrity in

attendance that evening, and I couldn't help but feel a little sorry for Samuel

L Jackson, in that my presence doubtless overshadowed his to a great extent.